Field Trips

Enhance your students' learning experience with an immersive and educational field trip to the museum, which tells the story of life in Texas from the formation of our planet, through the age of dinosaurs into our current time. Discounted rates are available for registered groups of 10 or more.

We encourage educators to contact TMMeducation@austin.utexas.edu for consultation and collaboration regarding planning educational activities for their future field trips.

See Group Rates

Learn more about admission prices and reservations.

Expectation Slides (PDF)

Download this presentation to prepare students for an upcoming field trip and help create an unforgettable museum experience.

Educator Resources

Create a more meaningful museum experience for students by using our library of TEKS-aligned PreK-12 educational activities based on the museum’s exhibits and specimens on display. These activity packets include lesson guides for educators and activity sheets for students, as well as sample responses and extension ideas. All activities are aligned to current and new Science TEKS going into effect fall of 2024.

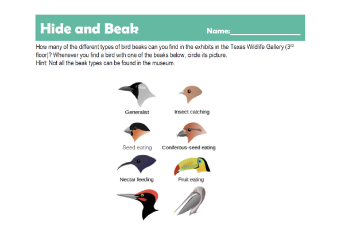

Hide and Beak

In this activity, students will describe the relationship between a bird’s anatomy, particularly its beak size and shape, and its feeding behavior and diet. This is an excellent example of the principle of “form fits function” observed in biology.

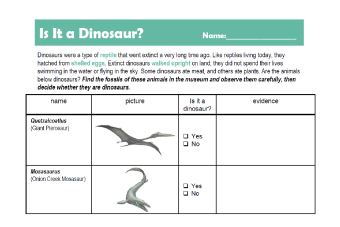

Is It a Dinosaur?

This activity addresses a common misconception young students have: that most fossils displayed in science museums belong to dinosaurs! Students will distinguish fossils as dinosaurs or non-dinosaurs using visible traits, drawings and information from museum labels.

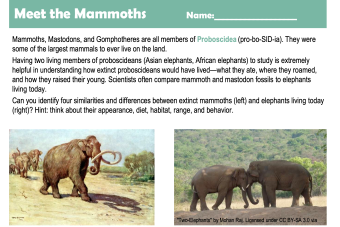

Meet the Mammoths

Students will compare extinct mammoths and modern-day elephants by listing the differences and similarities between their appearances, diets, habitats, ranges and behaviors. They will closely observe the teeth of a mammoth, mastodon and gomphothere and relate their structure to the animals’ diets.

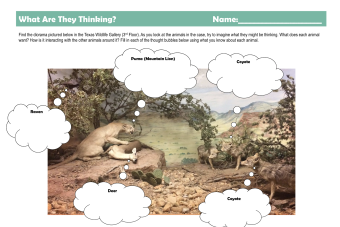

What Are They Thinking?

Students will observe an ecosystem on display, identify the predator/prey relationships among species, categorize animals as producers, consumers, carnivores, herbivores or omnivores, create a food web for the ecosystem and predict the effects of changes in the environment caused by living organisms, including humans.

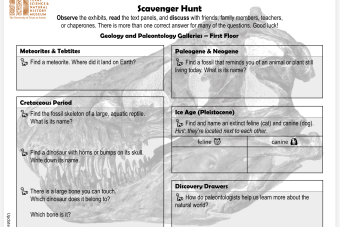

Scavenger Hunt

Download and print a scavenger hunt (in English and Spanish) prior to your visit or field trip!

Professional Development

Texas Science & Natural History Museum supports educators by offering a variety of professional development opportunities for formal and informal educators. All programs are free and provide TEA-approved CPE credit. For more information regarding professional development events contact TMMeducation@austin.utexas.edu.

Previous Event

A Time Before Texas: Free Virtual Professional Development

Volunteer at the Museum

Are you passionate about informal science education?

Volunteers on the Education team are called Gallery Guides. Gallery Guides interpret up-to-date and engaging scientific information to visitors to the museum's exhibit galleries, lead guided tours, participate in museum events, provide identifications of local fossils and ensure the exhibit components are not mishandled or damaged. Join us by applying to be a Gallery Guide. Please send your resume to TMMeducation@austin.utexas.edu and complete the application form.